The message wasn't from my lead. It was from someone in engineering I'd never spoken to.

Three words. Posted in a public channel at 7:43 AM on a Tuesday.

"I listen daily."

I stared at it longer than I should have. I don't remember what I said back. Something casual, probably. Something that hid the fact that I'd been refreshing Slack to see if there were any new reactions or comments more times that month than I will ever admit out loud.

Here's what happened: I was drowning.

Too many Slack channels. Too much context scattered everywhere. I kept showing up to meetings and realizing I'd missed something important, and the shame of not knowing was starting to harden into something worse.

I'm not good at asking for help. I'm better at building systems that make the asking unnecessary.

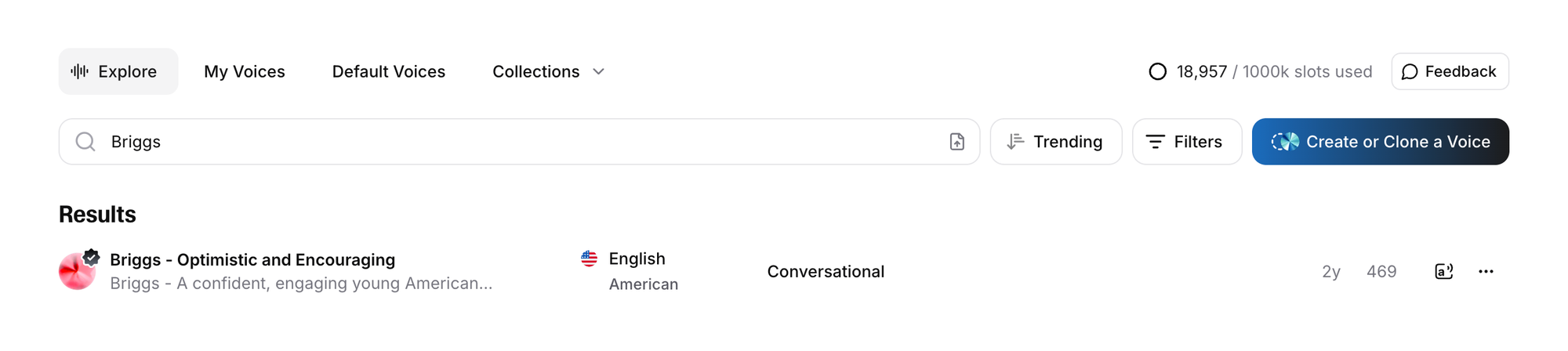

So I built a thing. A podcast that turns our company's Slack into a ten-minute morning briefing. Gemini for analysis, a separate prompt for the script, our own voice tech for the audio. By the time you pour my coffee, the briefing is waiting. Voiced by me. (Type "Briggs" into ElevenReader or ElevenLabs and you will see my voice clone sitting there ready to use, made for this project.)

I didn't tell anyone. Then, I told a few people. Then, I just started posting episodes in a channel and figured if people found it useful, they'd listen. If they didn't, I'd still have solved my own problem.

Almost half of the company listens now. No announcement. No mandate. No one asked them to.

I think about those three words a lot.

Here's what I've learned: internal tools die in a very specific way.

They don't explode. They don't get formally killed. They just... stop. Someone builds something useful, gets busy with other work, and the thing that required their attention quietly rots. People notice it's stale. They stop checking. Eventually someone asks "whatever happened to that thing?" and the answer is a shrug.

Cisco tried an internal radio channel years ago. Same basic idea—synthesize company information into audio. Good instinct. They abandoned it. Not because people didn't want it. Because someone had to show up every day and make it happen, and eventually that someone had other priorities.

That's the trap. The idea isn't the hard part. The sustainability is.

I think most internal initiatives fail because they're treated like favors.

Someone builds a tool, shares it with the team, and waits for gratitude. When the gratitude doesn't come—or worse, when people start requesting features—the builder gets resentful. I did this for free. I did this on top of my real job. Why are you asking for more?

Your colleagues are the most hostile user base you will ever face.

They didn't opt in. They're already overloaded. They will route around friction instantly. They have zero obligation to use your thing just because you made it. They're not customers who chose you over a competitor. They're people who showed up to work and found your tool sitting in their path like a tollbooth they didn't ask to pass through.

If you want internal adoption, you have to earn it the same way you'd earn it externally. Clear value proposition. Consistent delivery. Zero cognitive load. The kind of experience where using the tool is easier than not using it.

I treat my colleagues like customers. That's not a metaphor. That's the whole thing.

The Weather Report works because I refused to make it optional.

Not optional in the sense of mandatory—no one has to listen. Optional in the sense of variable. The episode ships every morning at the same time. The format is consistent. The voice is the same. The runtime is predictable. You know exactly what you're getting, which means you can build it into your routine without thinking.

I automated everything I could, and the rest is as easy as pressing a button before I leave my desk for the day. The data pull, the analysis, the script generation, the audio synthesis. It happens almost all with me barely touching it. The only real manual step is me occasionally tweaking prompts when I notice the output drifting. Otherwise, it runs whether I'm paying attention or not.

That's what killed the Cisco version. It required a human to show up and care every single day. Mine requires a human to have cared once—when building the system—and then the system takes over.

Automation changes which ideas are viable. The Weather Report isn't a better idea than what Cisco tried. It's the same idea with a different sustainability model. Same instinct, different infrastructure. Same dream, different bones.

The part I didn't expect was what happens when something crosses from "internal tool" to "thing people actually want."

A few weeks in, a customer reached out asking if they could build their own version. Not because we'd pitched it. Because someone on their side had heard about it from someone on our side and wanted to know if the capability existed.

Then another customer asked. Then a third.

I'd accidentally built something people would pay for by refusing to half-ass something I'd built for myself.

That's the pattern. The best internal tools aren't designed to be products. They're designed to solve a real problem for a real person—usually the builder—and they become products when other people recognize themselves in the solution.

The Weather Report started as a confession: I can't keep up with Slack and it's making me worse at my job. That's not a product pitch. That's embarrassing. But it turns out a lot of people have the same embarrassment, and some of them have budget.

I don't know if we'll productize it. That's a different conversation with different stakeholders and different tradeoffs. What I know is this:

Adoption is the only honest metric.

Not engagement. Not satisfaction surveys. Not the number of people who said "cool idea" in the launch thread and never opened it again. Adoption. Repeated use. The thing people reach for without being asked because it makes their life better.

Thirty percent adoption in a month, with zero marketing, tells me the problem is real. The customer requests tell me the solution travels. Everything else is stories we tell ourselves about why something should work.

There's a version of this essay that's about strategy. About internal tooling philosophy, about infrastructure layers, about treating colleague experience with the same rigor as customer experience.

But honestly? I didn't build The Weather Report because I had a thesis. I built it because I was overwhelmed and needed help. I built it because the alternative was admitting I couldn't keep up, and I'm not very good at admitting that.

The philosophy came after. After it worked. After people started listening. After I had time to reverse-engineer why.

That's how it usually goes. You build something because you need it. You keep building because it's working. And somewhere in the middle, you start telling a story about what you believe—but the belief came from the artifact, not the other way around.

But I shipped it.

It's working.

Half of the company wakes up to something I made.

For now, that's enough.

Internal tools fail because nobody treats caring as a system or sees it as useful.

Useful is better. Useful survives. Useful compounds.